Short summary: A recent preprint reports that use of Viagra and related drugs is associated with a lower mortality rate, raising hopes that it might be repurposed as a longevity therapeutic. Unfortunately, the methodology used in this and other recent studies is too weak to arouse too much excitement just yet.

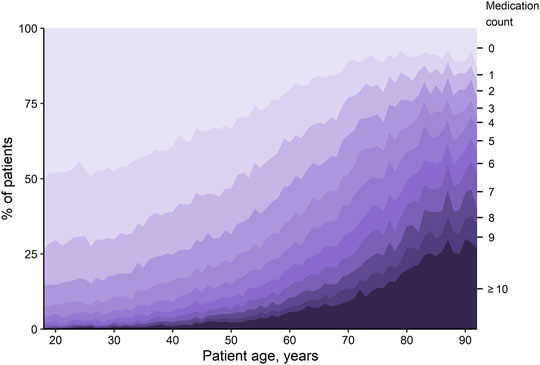

The FDA has approved more than 20,000 prescription drugs for marketing in the United States. Nearly half of all Americans — some 163 million — take at least one of them, and there are hundreds of top-selling drugs that are individually used by anywhere from the upper hundreds of thousands to tens of millions of Americans. It’s very reasonable to think that somewhere in that sea of pharmacological liferafts, there would be beacons that some drugs have unexpected benefits, including potentially anti-aging effects.

One potential way to identify such drugs is by spelunking among the associations between the use of particular drugs and later risk of all-cause mortality, since aging is by far the dominant cause of death in the United States and worldwide and since older people are the main users of most drugs. Simply put: do people who take some particular drug for a long time enjoy a lower death rate than would be expected from the drug’s known effect on disease?

But the longevity community has already chased itself breathless after one wild goose of this sort: the diabetes drug metformin, whose bona fides as a longevity therapeutic were given an enormous boost by a methodologically flawed epidemiological study that seemed to show that people with diabetes who were taking metformin had a lower risk of death than even nondiabetics who were not taking it. But this illusion was dispelled by studies that carefully untangled this methodological ball of yarn. Better-designed studies confirm that people with diabetes who take metformin are at lower risk of death than other diabetics taking different diabetes drugs (at least in most analyses), but still found that all people with diabetes are at higher risk than nondiabetics, whether they take metformin or not. In other words, metformin is a solid drug to help people with diabetes manage their disease — nothing more.

Now, a new study of this type has been released in preprint form by scientists associated with the biotech company Epiterna. Although the researchers are serious scientists and the method they used was as open-ended as they come, the headline results sound like the authors were cooking up clickbait: Viagra® (sildenafil) and various forms of medical estrogen will save your life!

This wasn’t the first time that a study has reported that either sildenafil (and other drugs in its class) or ERT appeared to have benefits against aspects of aging far beyond what they were actually approved for. But as we’ll see, this new report isn’t particularly convincing evidence for such benefits, and there are related problems with the previously-published studies.

What They Did

The Epiterna group took advantage of an amazing resource established in the UK but available to scientists all over the world:

The UK Biobank(UKBB) is a large-scale biomedical database and research resource containing de-identified genetic, lifestyle and health information from half a million UK participants. More precisely, it contains prescription medication data, together with mortality data in the general UK population, in adults aged 37 to 73, for over 500,000 subjects.

To mine the data for possible longevity therapeutics, the researchers narrowed the exhaustive list of drugs used by people in the database down to those that at least 500 people took for at least three months (although how they went about doing that led to some results they probably didn’t intend). There were many more drugs in the database that didn’t make the cut, but if they had looked at drugs that only a very small number of people took, it would increase the odds that they would be led astray by a few outliers or random variations.

For the 406 drugs that met these criteria, the authors matched each user of a given drug with a control person who was not using it, but who was similar to them in things that increase one’s risk of death for other reasons, such as older age, specific diseases, male sex, smoking, and low socioeconomic status. The idea was to minimize differences between users and nonusers of a given drug that might affect users’ death rates for reasons unrelated to the drug itself.

For example, people in the study who used atorvastatin (Lipitor®) were, on average, older than the rest of the UKBB population, and were more likely to be male and to have diabetes. Each of these things reduces a person’s life expectancy independently of the drug, so to account for that, the researchers matched each Lipitor user to a statistical doppelganger with a similar risk profile. The hope was that by accounting for these risks, any remaining increase or decrease in mortality risk among users of Lipitor would be more likely to be due to the drug itself instead of being a product of the risks associated with their personal characteristics.

So far, so good. Unfortunately, the researchers only adjusted for a subset of the lifestyle and other personal information that the UKBB collects about its participants. And the UKBB itself doesn’t have some of the information on its subjects that we might need to avoid falling into artificial associations between the use of certain drugs and a person’s risk of death. As we will see, there are many cases in this study where there is good reason to think that the association between the use of a particular drug and mortality is actually the result of the way the typical user of that drug lives his or her life rather than of the drug s/he is taking.

A Swimming Expedition

The most obvious case where such confounding is likely at play is the association of a drug product called Otomize with a 12% lower risk of death. Otomize is a combination antibiotic and antiinflammatory spray used to treat swimmer’s ear (AKA otitis externa), an infection of the ear canal that most often afflicts frequent swimmers. People squirt Otomize on the outer surface of the inner ear for a few days to kill bacteria and dampen swelling, and then they stop using it and get on with their lives. Now ask yourself: is it really likely that such a drug would cut a person’s risk of death by 12% every year for up to four decades?*

Instead, a more biologically plausible explanation for the association lies with the kind of people who would use more than one course of this drug: regular swimmers. Few people will develop swimmer’s ear if they don’t swim frequently, and for people to be counted as Otomize users in the preprint study, they had to have taken at least two separate courses of it over decades of observation. All of this testifies to an ongoing discipline of swimming.

And frequent, long-term swimmers are disproportionately healthy. Most people will only make a regular habit of swimming if they’re in good physical health to begin with: many people who are physically debilitated or mentally incapacitated could build some kind of swimming into their weekly routine, but very few such people do. And regular swimming builds up your cardiorespiratory fitness, which is powerfully associated with lower mortality rates. Thus, a strong potential explanation for the finding that Otomize users have lower death rates than other UKBB participants is that Otomize users are likely to be physically fit and conscientious people.

In most modern epidemiological studies, researchers would account for this confounding factor by building statistical models that incorporate each person’s exercise habits (or, better yet, their cardio fitness as measured directly on a treadmill test or the equivalent). If they had done that in this study, they would have matched each Otomize user with a statistical ”twin” who did not use Otomize but who had similar cardio fitness. Unfortunately, although UKBB includes a somewhat crude measure of all physical activity and has fitness tracker data on a subset of participants, the authors of this preprint didn’t incorporate these data into their model.

This is not because the Epiterna researchers just didn’t think to look at exercise: instead, the researchers found that many of the people they included in their analysis were missing their physical activity scores. And when they looked at the relatively small number of people for whom they had the activity score, this one variable in isolation didn’t seem to move the needle on mortality for the UKBB study population as a whole. So they consciously chose to exclude it. Meanwhile, for reasons that are unclear, they didn’t use UKBB fitness tracker data, and UKBB does not directly measure participants’ cardiorespiratory fitness. So while we have every reason to believe that Otomize users were predominantly frequent swimmers, we have no way to directly test the role of exercise in their results.

Another thing that makes this study structurally vulnerable to such artifacts (if indeed that’s what this was) is that the authors included drugs in their analysis to which people had only minimal exposure, so long as enough people used them. Specifically, people had to have filled at least two prescriptions separated by at least three months. That meant that people who had been taking a statin every day for decades would be lumped together with (for example) people who had taken the same drug for three months and then quit.

It would be very surprising for a drug to which a person had no more than a few months of exposure to have shifted the trajectory of their biological aging process for decades after they stopped using it. Conventional drugs work by altering a person’s day-to-day metabolic processes, and the biological effect (and its impact on downstream consequences) disappears when one stops taking it, whether it’s blood pressure drugs, or statins, or GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic® and Wegovy®). Thus, to have an enduring effect on a person’s survival over the course of a study as long as the UKBB, a person would usually have to be taking a given drug regularly throughout those years (and therefore keep pushing their metabolism in the desired direction). And you would expect the same to be true of a hypothetical old-school gerotherapeutic (like rapamycin).†

At the extreme end, the Epiterna researchers’ three-month bookend method led them to include drugs of which people had only ever taken two doses (or two short courses) separated by months or even years. This is exactly the way people typically use Otomize, though we don’t have this broken down in the paper. Otomize is a drug for short-term use to clear up an acute problem, which again suggests that something other than the biological effect of the drug itself is responsible for its association with a lower risk of death.

And on top of that, the fact that people’s prescriptions for a course of Otomize were only included in the analysis because they are typically separated by months or years introduces a well-known artifact-generator known as the immortal time bias. This happens because people can only count as part of the Otomize-user group if they survive the time between their first and second prescription. Those who die in the meantime simply disappear from the study.

Going There

By now, you may have guessed that I suspect that a similar mirage underlies the Epiterna preprint’s star finding. Is it really true that using Viagra and its cousins decimates a person’s risk of death? Or is there something about sildenafil users that might protect them from death, independent of the drug itself?

On its face, it’s not completely crazy to think that PDE5i might somehow protect people from death. Indeed, that’s what they were originally expected to do when Pfizer scientists got to work developing them. Viagra (sildenafil) and related drugs like tadalafil (Cialis®) and vardenafil (Levitra®) work because they inhibit the enzyme phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5). This enzyme breaks down messenger-molecules that tell the cells lining blood vessels to open up and allow in blood flow. By preventing PDE5 from breaking down this messenger, these PDE5 inhibitor (PDE5i) drugs let the messenger-molecule hang around to do its job relaxing blood vessels, thereby allowing more blood to pass through.

Opening up a person’s arteries could hypothetically benefit people’s health in many ways. Pfizer originally developed sildenafil expecting it to be a new way to treat high blood pressure. It turned out to be too hard to work with for this purpose, but early trial volunteers serendipitously discovered that it worked well for ED. The same mechanism makes PDE5i effective in treating pulmonary hypertension, an awful disease in which the artery that delivers blood from the heart to the lungs to pick up oxygen gets strangled, leading to shortness of breath, fainting, swelling of the ankles, and — eventually — heart failure and an early death. And as we’ll see, scientists have even looked into PDE5i as a potential way to treat age-related cognitive decline and dementia by (hypothetically) increasing the flow of blood to the aging brain.

But when we come up against the finding of an association between use of PDE5i and lower mortality risk in the Epiterna preprint, we need to ask the same kind of question we asked about the similar but more counterintuitive finding about the topical antibiotic Otomize. What kind of people use PDE5i, and how are they systematically different from the rest of the population?

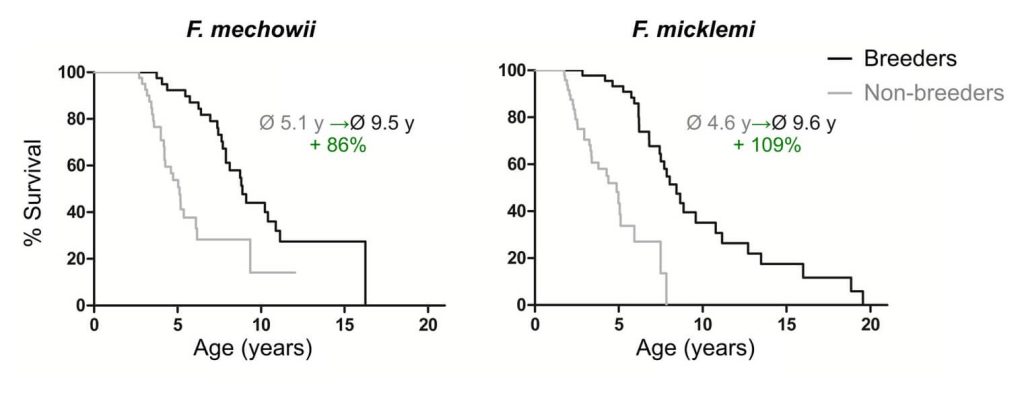

The overwhelming majority of PDE5i users are taking it for ED, of course — and in this paper, the authors only looked at male PDE5i users, so the scant few women taking Viagra for pulmonary hypertension are not playing into the results. Long-term repeat users of Viagra are almost by definition regularly sexually active, and more frequent sexual activity and more frequent male orgasms are powerfully associated with lower risk of death from all causes. A similar association also seems to hold in the famed naked mole rat (NMR), although the unusual reproductive structure of NMR populations may mean that the reasons in that species may not apply to humans. The frequency of the male orgasm has been linked to reduced risk of prostate cancer, and people who have sex more frequently in the two decades after a heart attack are less likely to die. Even a lack of interest in sex in men over 40 is associated with elevated risk of dying.

Some of these associations may be the result of emotional intimacy or psychological factors that swirl around sexual relationships rather than sexual acts themselves. Being regularly sexually active in middle age and beyond tends to mean (not always, of course) that a person is either in a stable, loving, sexual relationship or has the optimism and confidence to play the singles game successfully. And we know from many studies that being married is associated with a lower risk of death (especially in men), dementia, and many other diseases of aging, whereas being lonely appears to be roughly as big a risk for premature death as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. Moreover, many users of sildenafil report that it improved their relationship with their partner and their emotional well-being; conversely, conflict with their partner is one of the top reasons for men discontinuing PDE5i.

Further stacking the deck in favor of the PDE5i user group, there are many men who have ED but who never seek out a prescription for these drugs, either because they are involuntarily single (and likely lonely) or because their relationship with their spouse is dysfunctional. Such men are at high risk, based on the studies we’ve just breezed through. The same would be true of many men who fill one prescription and then drop it after a failed attempt to rekindle sexual intimacy. The way the Epiterna study is set up, such men would be counted as potential matched controls for PDE5i users, stacking disproportionately partnered and fulfilled men against disproportionately lonely or unhappy ones.

And on top of these emotional and interpersonal confounders, a man would not typically take a PDE5i if he had health or mobility challenges that would limit his participation in sexual activity irrespective of his ED, making their use yet again a marker of broader physical health.

Since regular sexual activity has been associated with as much as a 50% cut to one’s risk of death, it’s easy to see how confounding with these personal characteristics of PDE5i users could be responsible for the modest 15% reduction in risk of death associated with use of PDE5i that the Epiterna researchers report, instead of it being due to the effects of the drugs themselves. The same is true of a somewhat more methodologically rigorous observational study linking PDE5i use to lower risk of heart attacks and other severe cardiovascular problems in people with high atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk factors. And as with the effects of swimming, the authors did not or could not adjust for even marital status, let alone the more intimate question of the quality and character of men’s romantic lives.

One way that the authors of the preprint study could in principle have greatly reduced the risk of such confounding would have been to match users of PDE5i with users of other drugs to counteract ED. If they had been able to match subjects that way, both the PDE5i users and the matched comparison subjects would likely have been similar to each other in the personal characteristics associated with the use of such drugs, allowing any purely pharmacological effect of PDE5i to shine forth more clearly. Unfortunately, this approach isn’t possible, because there just aren’t any other drugs to treat ED: the PDE5i are literally in a class by themselves.‡

You’ve Got it On the Brain

There are similar problems in several well-publicized studies that have found an association between the use of PDE5i and reduced risk of neurodegenerative aging of the Alzheimer’s type (Alzheimer’s). One well-publicized study using Medicare claims data from 7.23 million people found that use of sildenafil was associated with a remarkable 69% reduction in the risk of Alzheimer’s!

But here again, the the authors didn’t do anything to account for the confounding personal characteristics associated with regular use of an ED medication. The authors chose to compare users of PDE5i to users of four different drugs (diltiazem, glimepiride, losartan and metformin). The rationale was that other researchers are investigating two of these drugs (losartan and metformin) as potential therapies to protect against Alzheimer’s, so the authors figured that they were comparing one candidate Alzheimer’s prophylactic against several others.

In the case of metformin, this effort is likely doomed to failure — but that isn’t the central problem with using users of these drugs as a comparison group for PDE5i. As researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill pointed out, none of the comparison drugs are used to treat ED, and doctors aren’t currently prescribing losartan or metformin as Alzheimer’s-prevention pills. Instead, losartan and metformin are used by people with entirely different health concerns and personal characteristics from PDE5i users. Comparing PDE5i users to users of these alternative drugs therefore doesn’t get at the question of confounding — with sexual activity itself, with loneliness, or with general good health — that we discussed above. Marriage is associated with lower risk of dementia, while loneliness is associated with increased risk, and regular sexual activity and sexual satisfaction are associated with slower cognitive decline. Thus, the same kind of personal confounding in PDE5i users that we discussed in the mortality study remains a likely explanation for the association between PDE5i use and reduced risk of dementia.

After a back-and-forth with the UNC Chapel Hill researchers in the letters column of the Nature Aging journal, the authors agreed to issue a correction that more accurately characterized the role that their comparison drugs played in the analysis — but they left the analysis itself standing. A later study by the same authors used slightly better comparison drugs, but still failed to grapple with the distinct personal characteristics that likely separate most PDE5i users from people who use these other drugs.

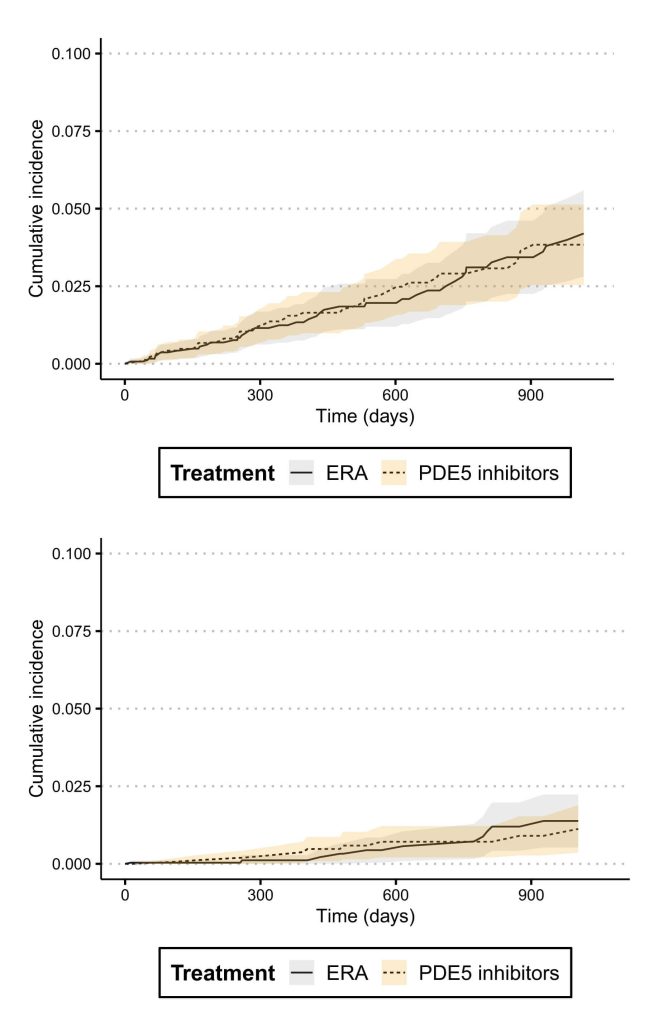

Fortunately, a group of researchers from Harvard, the National Institute on Aging (NIA), and elsewhere came at the same question from an angle that bypasses all of these problems. This ”Drug Repurposing for Effective Alzheimer’s Medicines” (DREAM) team looked specifically at people who were using PDE5i for pulmonary hypertension (PH), not ED. Focusing on the PH indication jettisons the lifestyle baggage associated with the use of PDE5i for ED. As we’ve just discussed, men using PDE5i for ED tend to differ in critical ways from men the same age who aren’t using them. And while there are no good alternative drugs for ED whose users could be compared to PDE5i users, people with PH can choose among several classes of drugs to manage their condition.

So by comparing people with PH who manage it with PDE5i to people with the same condition who use an entirely different class of drugs (endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs)), the DREAM investigators could make apples-to-apples comparisons. Because all PH sufferers share the same health condition in common, any major difference in the risk of Alzheimer’s between people with PH who treat it with PDE5i versus those who treat it with ERAs is more likely to be the result of the drug itself rather than underlying differences in the kind of people who use PDE5i and those who don’t. And to further tighten up the analysis, the DREAM researchers further controlled for 76 additional confounding factors, including age, race, gender, low income, smoking, and various diseases, as well as running analyses to double-check for specific sources of methodological will-o’-the-wisps.

The result: “across four separate analytic approaches designed to address specific types of biases … we observed no evidence for a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors”.

The DREAM researchers paired their observational study with experiments in which they dosed neuron-like cells and brain immune cells with sildenafil in culture. This was to double-check and expand on previous researchers’ findings that sildenafil has effects on cells that might be protective against neurodegenerative aging of the Alzheimer’s type: things like beta-amyloid secretion and a modification of the protein tau that is involved in the disease. These tests largely came out empty, or with results that are too small to plausibly have an important effect on a person’s risk.

Meanwhile, other researchers have looked at the main mechanism that originally got scientists thinking that PDE5i might be protective against dementia: the idea that Viagra & co. might increase blood flow to the brain. While there are limits to what these studies can tell us, it appears that PDE5i modestly improve the regulation of blood flow in the brain, with most of the benefit occurring in people whose brain blood vessel function is already impaired. Whether that’s enough to move the needle on the aging of a person’s brain will require longer-term studies.

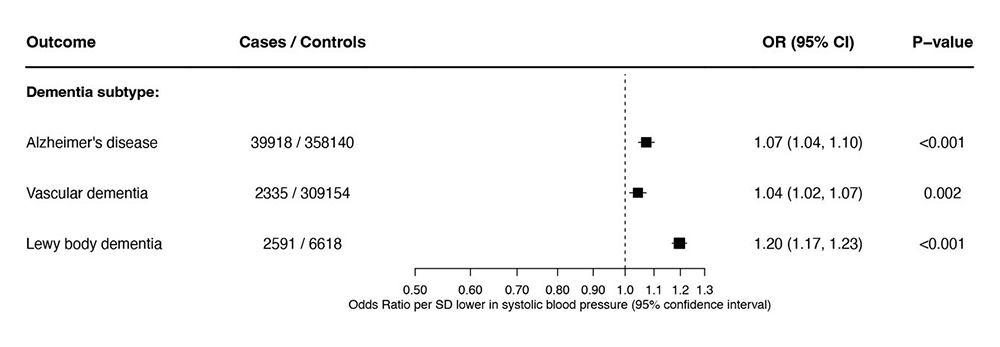

Separately, other researchers have tried to get around the differences in lifestyle between most PDE5i users and the rest of the population using a relatively new tool: Mendelian randomization (MR). Because people randomly inherit the genetic variants that impact how active some biochemical pathway will be in them, Mendelian randomization divorces the biological effects of a higher or lower activity of that pathway from the lifestyle and environmental influences on it. MR thus acts as a simulated randomized trial of the long-term effects of a drug or other intervention that modulates that same biological pathway on a person’s long-term health (in this case, the impact of PDE5i against Alzheimer’s). The first study of this kind found that the genetic equivalent of PDE5i slightly increased people’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia, as well as reducing the thickness of their brain tissue and their near-term cognitive performance!

Firmer Ground

While the new preprint’s PDE5i findings are on shaky ground, other findings seem more credible. For instance, they found that SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i)— a relatively new class of diabetes drugs — were associated with impressive reductions in the risk of death: a remarkable 34%, as compared to 15% for sildenafil. One key thing that makes this finding more credible than the problematic PDE5i result is that the Epiterna researchers compared people who used SGLT2i against other people who share their key health problem: diabetes. As with the study that compared people who use PDE5i for PH with other people who used other drugs to treat the same condition, this ability to match diabetic users of SGLT2i with diabetics who rely on other drugs makes for a more apples-to-apples comparison, giving us more confidence that these drugs are, at least, potentially much more protective against death than other diabetes drugs.

It’s important to note that because the Epiterna researchers matched people by diabetes status, the preprint study doesn’t tell us that SGLT2i users had lower death rates in people without diabetes, and there is no separate breakdown of mortality rates in nondiabetic SGLT2i users (if there were any) to compare with nonusers without diabetes. However, there is a lot of other evidence to suggest that SGLT2i might have wide anti-aging effects. Although designed as anti-diabetes drugs (they cause you to lose blood sugar into your urine), SGLT2i also effective in protecting people with kidney disease against catastrophic kidney outcomes — and crucially, this is true regardless of their diabetes status. Similarly, SGLT2i keep people with heart failure from dying or being hospitalized for heart failure, whether they are diabetic or not. And one specific SGLT2i (canagliflozin) extends lifespan and slows the accumulation of aging defects in the heart, kidney, liver, and adrenal gland in male (but not female) mice.

Another finding in the Epitena preprint in which we can have more confidence than the PDE5i association is that users of many estrogen-based drugs had much lower death rates than nonusers. Most of these drugs are forms of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for perimenopausal women, though the birth control pill Marvelon also had such an association.

If this were the first report of lower risk of death in users of these drugs, we’d be justified to be as skeptical as we have been for PDE5i. Historically, women who use HRT have been more educated, thinner, of higher income, and more likely to exercise than women who don’t; they have also been more likely to drink alcohol, which is itself associated with lower risk of ASCVD (although this relationship is itself likely an artifact of study design). And like PDE5i, HRT is prescribed when a person goes to their doctor looking for help, unlike many other medications where a doctor picks up a problem after a blood test or other diagnostic tool. This means that HRT users are more likely to have health insurance (not an issue in the UK), to be in active contact with their doctor (and thus to have other problems noticed and taken care of), and to have the money to pay for a drug for a non-life-threatening condition.

Since the Epiterna study can’t account for any of these systematic differences, this study alone shouldn’t give one much confidence that HRT is beneficial outside of alleviating menopausal symptoms. But despite the possible role of such confounders in the Epiterna preprint result and the long and tortured saga of HRT and risk of diseases of aging, we can be confident that HRT as women most often use it (early in (peri)menopause to address menopausal symptoms) really does lower overall risk of mortality, because we have randomized controlled trials to show it.§

Full Circle

We started this post by reminding ourselves of the illusion of longer-than-nondiabetic life expectancy in diabetic users of metformin in other studies. Because metformin is the first-line therapy for diabetes, there are more than enough long-term metformin users in the UKBB database for that drug to get its own analysis in the Epiterna preprint. Acknowledging the many limitations of the methodology used in the study, their finding was that metformin users died at the same rate as nonusers of metformin. That’s in line with what more sophisticated studies of metformin and mortality have found. As we discussed earlier in this post, other diabetes drugs like SGLT2 inhibitors and also acarbose have shown much more promise in human and animal studies.

We’ll have more information on much of this in the coming years. The companies that make different SGLT2 inhibitors are setting up trials to test them for new indications, including following up on promising observational evidence that SGLT2i may improve survival in people with the common form of lung cancer. (On the other hand, we learned while this blog post was in preparation that SGLT2i failed to prevent later death or hospitalization for heart failure in people who had recently had a heart attack). After a generation of women were scared off of HRT by widespread overreaction to the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial, HRT use has risen substantially in the younger, symptomatic women for whom it is indicated, though we are unlikely to ever get another HRT trial as ambitious as WHI. While it’s still far from funded and likely to fail if it gets going, the longevity biotech sector could still mine silver linings from the TAME trial of metformin.

As we’ve seen, the association of PDE5i use with a modest reduction in all-cause mortality is likely a chimera: what we are likely seeing is that the kind of people who use PDE5i for ED enjoy a low death rate because of their behaviors and baseline health, refracted through the prism of their associated use of a distinctive drug. Unfortunately, the vast majority of clinical trials for PDE5i for ED have lasted 8-12 weeks, meaning that we can’t mine existing randomized trials for an effect on mortality. And no “TAME for Viagra” trial is likely. (On the other hand, there’s an ongoing trial of a PDE5 inhibitor to improve cognitive function in people with Alzheimer’s dementia underway in Korea, though the evidence we’ve reviewed suggests that its prospects are dim).

We should in any case keep our eyes on the prize. If real, a 15% reduction in mortality would be meaningful, but also constrained by the inherent limitations of any drug that merely adjusts the rheostat on the amount of cellular and molecular aging damage inflicted by one metabolic pathway or another. As we’ve discussed before with other examples, even if PDE5i work as well as implied by the Epiterna preprint, such broad metabolically-based therapies have a hard ceiling on their benefits.

By smashing through the biological glass ceiling of the limits of our evolved biology, damage-repair therapies open the horizon of an ever-greater human healthy lifespan. We should all be happy if PDE5i turn out to have some modest potential to keep us alive and healthy for longer, but the unlimited potential of directly repairing aging damage to keep people young and healthy is why SENS Research Foundation exists.

* It is not clear from the preprint how long users of any given drug were actually followed up or if the investigators took account of the age at which a given subject began using a drug or how long he or she took it; all of these are important drivers of the long-haul effects of a drug.