Short summary: Metformin has been proposed as an “anti-aging drug,” and a major clinical trial is about to get underway to test the idea. In the first post in the series, we reviewed the animal data (especially lifespan studies) examining this question. In part two, we look at human studies on metformin in diabetes prevention and flawed observational studies that suggested that it reduced risk of diseases of aging and even increased life expectancy in nondiabetic people.

Human Studies: Compared to Whom?

The study that is most often cited as evidence that metformin slows the aging process in humans was released with a press release misleadingly titled “Type 2 diabetics can live longer than people without the disease.” But the underlying study[1] had a design flaw that first unintentionally selected only the healthiest diabetic patients (those on metformin) and compared them to patients with poorer glycemic control (those on other drugs) and a random assortment of the nondiabetic population — and then systematically pushed subjects on metformin “off the books” as soon as their diabetes progressed.[2],[3]

Because they wanted to compare people taking metformin to people who were not, the authors of the study removed subjects in the “metformin only” group from the analysis as soon as they started using additional diabetes medications. But diabetic patients are normally given metformin as their very first drug, with additional drugs being added on when the disease gets worse. By removing people who were initially taking just metformin from the analysis if they added on additional drugs during the course of the study, people whose diabetes got worse on metformin were systematically weeded out of the study.

But meanwhile, there was no such censoring of the other groups; consequently, when the study was over, the study scientists were comparing (a) an elite subset of people who began the study using metformin and continued to use it and no other diabetes drug group for an average of five additional years; (b) other diabetics who had worse disease and needed more intensive diabetes medication to control their diabetes from the outset; and (c) aging nondiabetics. So through a kind of methodological ratchet effect, the analysis only retained the healthiest metformin users, while people in the latter two groups remained in the study as they followed the normal trajectory of diabetic or aging people over time, getting sicker and sicker over the course of the study.[13],[14]

This way of analyzing the data accidentally thereby introduced a kind of survivorship bias into the study. As a result, the lower death rates in the metformin group as compared to the other two groups were in all likelihood the result of the design flaw in the study, not a special protective effect of the drug.[13],[14]

The same problem (or related ones) have plagued most of the observational studies that you may have heard cited as showing that metformin lowers the risk of atherosclerosis, total mortality, and especially cancer.

Drawing inferences from such studies about effects on aging in otherwise-healthy people would thus be misguided even if these studies didn’t share this design flaw, since none of these other studies include a separate group of people without diabetes. Rather, such studies have compared metformin-taking diabetic people to other people with diabetes taking other diabetic drugs. At best, such studies may imply that if you’re diabetic, it may be a better choice to milk as much as you can out of metformin before adding on injected insulin or drugs like sulfonylureas that push the body to release more insulin of its own.

But actually, even in such diabetics-only studies, the apparent benefits of metformin vanish when the studies are designed to avoid survivorship and selection bias.[4],[5],[6] Indeed, even in diabetic patients, actual clinical trials (as opposed to observational studies) find that metformin is no better than other diabetes drugs at preventing or slowing the course of cardiovascular disease.[7]

TAME: The Prequels Suck

In the midst of all the hype about TAME, it’s surprising how little attention has been afforded to the fact that a significant number of clinical trials testing metformin in nondiabetic, aging humans have already been done! And consistent with the rodent lifespan studies, these trials suggest that TAME is “not the anti-aging drug you’re looking for,” any more than Star Wars fans’ pent-up demand for new adventures with their heroes were fulfilled by Jar Jar Binks.

When put to the test in human trials, metformin has no effect on blood sugar control in obese women with normal glucose tolerance[8] and only modest effects on fasting glucose in normal-weight, nondiabetic men.[9] Even in people who are on the path to diabetes, decidedly non-heroic exercise programs with modest dietary improvement outperform metformin at holding off the development of the full-blown disease.[10],[11],[12] In such prediabetic people, such a minimal lifestyle intervention is also more effective than metformin at lowering cardiovascular risk factors without the use of specific medications like statins or blood pressure drugs.[13] Similarly, exercise but not metformin tames glycemic variability (dangerously wide swings in blood sugar over the course of the day) in prediabetic people.[14]

And importantly, adding metformin to such lifestyle interventions doesn’t lower the risk of developing diabetes any more than lifestyle all by itself.[21],[22] Similarly, while both exercise and metformin do each improve a number of metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease, combining the two confers no further benefit.[15] In fact, most (though not all[16]) studies have found that taking metformin actually blunts the beneficial fitness and metabolic adaptations to both aerobic[15],[17],[18] and strength-training exercise[15],[19],[20] in older or prediabetic adults (see also the more preliminary studies reviewed in reference (21).

These were all short-term studies — but we do have long-term data from the followup of a large randomized controlled trial of the effects of metformin on frailty in aging people with prediabetes. When researchers followed up 12-14 years later, people who been randomized to take a sugar pill along with moderate diet and lifestyle reforms cut their risk of becoming frail in the next ten years by nearly 40% as compared to people taking a placebo but who were not assigned a lifestyle intervention. But those who were given real metformin tablets without a lifestyle intervention did no better than the controls — even though for much of the remaining time, they could opt in to the lifestyle program.[23]

And similar to its apparent effects on exercise gains, metformin may also blunt some of the benefits of a healthy diet, as we’ll discuss in Part 4 of this series. So far from being one more tool in the toolbox that an otherwise-healthy aging person draw upon to further their healthy-lifestyle efforts to stave off secondary aging, metformin appears to actually get in the way of people realizing those gains.

A TAME Spoiler?

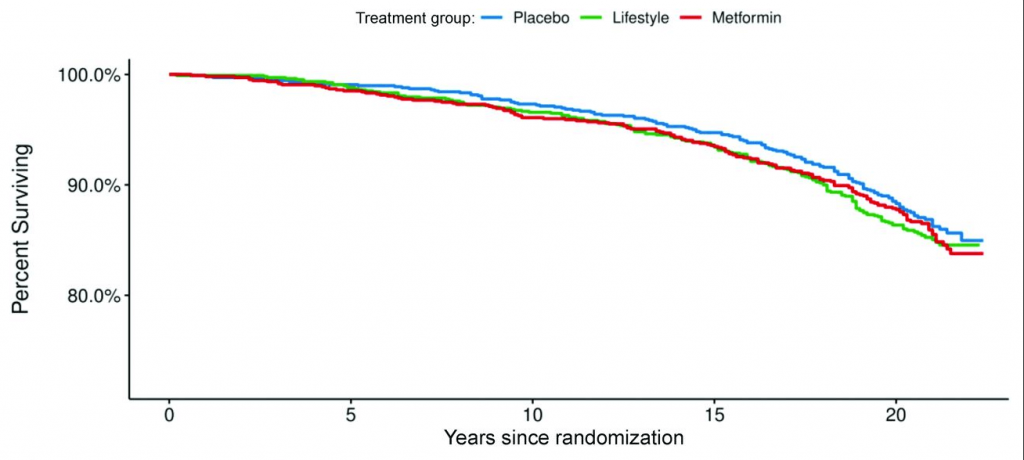

In Part 1 of this series, we saw that metformin repeatedly failed to extend life in well-designed rodent studies. And as we’ve discussed above, a study trumpeted as showing that people with diabetes taking metformin live longer than people without diabetes not taking the drug was the product of a faulty design. TAME will not be directly testing the effect of metformin on lifespan, for reasons we’ll discuss in Part 5 of this series, but you may be surprised to learn that there has already been a trial with followup that gives fairly long-term human data on mortality in a group of people who were not yet diabetic — and again, metformin came up short.

This was report from the long-term follow-up of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), a randomized controlled clinical trial that included more people than will be used in TAME (3,234 volunteers). The volunteers in the DPP were on average 50 years old, and all had prediabetes, which made them more likely to benefit from metformin than are the people in TAME, who will be otherwise-healthy but suffering from degenerative aging.

Subjects in the DPP were divided randomly into three groups. One group was given metformin tablets, along with standard advice about healthy diet and exercise. Another group was given the same guidance, but a dummy pill instead. And a third group also received the dummy pill, but were also enrolled into a healthy lifestyle program (rather than just being given general guidelines). This was not an elite lifestyle medicine program with free superfoods and a personal physical trainer, but sessions where they were encouraged and guided to get 150 minutes of exercise per week (including walking) and practice the low-fat portion-control diet typical of health guidance in the 1980s and 90s, with the aim of a 7% loss of weight.

The DPP itself lasted only 2.8 years, but the researchers at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases followed up with the participants at 10, 15, and as much as 20 years later. And to get to the punchline, people who had been taking metformin lived no longer than people in the control group.[24]

If metformin fails to slow aging enough to affect mortality rates over a 20-year period, as 50-year-old prediabetic people age out to become septuagenarians, how can it reasonably be expected to slow aging in people who don’t already have a good rationale for metformin as a way to address their prediabetes?

Metformin and the Heart

As with diabetes, a number of clinical trials have also tested metformin’s ability to protect cardiovascular health, and they have almost universally come back empty. The most important of these was the CAMERA trial, in which the same dose of metformin that will be used in the TAME trial was tested in a randomized, controlled trial in older people without diabetes, but with coronary heart disease. After a year and a half on the drug, atherosclerosis worsened at the same pace in people taking metformin as it did in people taking the placebo.[24]

In the GIPS-III trial, nondiabetic patients who had suffered a heart attack and had had a stent placed in their coronary artery were then given either metformin or a placebo, at random. This was prompted by animal studies in which the hearts of mice given simulated heart attacks recovered better if the mice were given metformin afterward. But in the human trial, people who received metformin were no less likely to suffer loss of heart-pumping effectiveness than people receiving a placebo.[25] Their hearts also suffered no less damage,[26] and over the course of the two years following their original heart attack, the metformin-treated subjects suffered just as many new heart attacks as did placebo-treated controls.[27]

Another small trial that gave people with prediabetes who didn’t already have CVD either metformin or a placebo had similar results. While metformin had some very small effects on different blood tests, it had no effect at all on actual cardiovascular events like heart attacks and strokes, and didn’t improve quality of life.[28] The same basic upshot also emerged in an earlier meta-analysis of clinical trials on the effects of metformin on cardiovascular disease that mostly included people with diabetes, but also included some nondiabetics.[29] Indeed, as we noted earlier, even in people who do have diabetes, clinical trials find that metformin is no better at preventing or slowing the course of cardiovascular disease than other diabetes drugs.[18]

We should get an even more definitive answer on whether metformin protects cardiovascular health in aging but nondiabetic people long before TAME is complete, thanks to the VA-IMPACT trial. With 3000 subjects being enrolled, VA-IMPACT will be the largest trial of metformin in nondiabetic people other than TAME itself. The earlier CAMERA trial[22] monitored the effect (or, as it turned out, lack of effect) of metformin on the progression of atherosclerotic lesions in the volunteers’ arteries, but didn’t last long enough or have enough subjects to confidently rule in or out an effect on more life-changing cardiovascular outcomes like heart attacks and strokes. VA-IMPACT will use its size and duration to answer that exact question.

But I wouldn’t hold my breath. It’s certainly true that some smaller or less-controlled trials have reported effects on different cardiovascular outcomes, but the best available evidence seems to fairly clearly rule out a substantial protective effect of metformin against cardiovascular disease in nondiabetic people.

Probably the reports about purported benefits of metformin in people without diabetes that have garnered the most interest from people outside of prolongevists have been those that suggested it might prevent or treat cancer. That evidence, too, has been followed up into the gold standard test of human clinical trials in nondiabetic people — and here again, metformin has failed to live up to the misguided expectations. That’s the subject of the next post in this series.

Citations:

[1] Bannister CA, Holden SE, Jenkins-Jones S, Morgan CL, Halcox JP, Schernthaner G, Mukherjee J, Currie CJ. Can people with type 2 diabetes live longer than those without? A comparison of mortality in people initiated with metformin or sulphonylurea monotherapy and matched, non-diabetic controls. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014 Nov;16(11):1165-73. doi: 10.1111/dom.12354. Epub 2014 Jul 31. PMID: 25041462.

[2] McConway K. Expert reaction to study looking at type 2 diabetes, metformin and lifespan. Science Media Centre. 2014 Aug 8. Online resource: http://www.sciencemediacentre.org/expert-reaction-to-study-looking-at-type-2-diabetes-metformin-and-lifespan/ . Accessed 2022-06-22.

[3] Margulis MV, Pladevall M, Riera-Guardia N, Seeger J, Patorno E, Varas-Lorenzo C. Comment on: Can people with type 2 diabetes live longer than those without? A comparison of mortality in people initiated with metformin or sulphonylurea monotherapy and matched, non-diabetic controls. PubPeer. 2016 Mar. Online resource: https://pubpeer.com/publications/4E29C6C9E32D2C24662AED78A59AC5 Accessed 2022-06-22.

[4] Farmer RE, Ford D, Mathur R, Chaturvedi N, Kaplan R, Smeeth L, Bhaskaran K. Metformin use and risk of cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cohort study of primary care records using inverse probability weighting of marginal structural models. Int J Epidemiol. 2019 Apr 1;48(2):527-537. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz005. PMID: 30753459; PMCID: PMC6469299.

[5] Tsilidis KK, Capothanassi D, Allen NE, Rizos EC, Lopez DS, van Veldhoven K, Sacerdote C, Ashby D, Vineis P, Tzoulaki I, Ioannidis JP. Metformin does not affect cancer risk: a cohort study in the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink analyzed like an intention-to-treat trial. Diabetes Care. 2014 Sep;37(9):2522-32. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0584. Epub 2014 Jun 4. PMID: 24898303.

[6] Stevens RJ, Ali R, Bankhead CR, Bethel MA, Cairns BJ, Camisasca RP, Crowe FL, Farmer AJ, Harrison S, Hirst JA, Home P, Kahn SE, McLellan JH, Perera R, Plüddemann A, Ramachandran A, Roberts NW, Rose PW, Schweizer A, Viberti G, Holman RR. Cancer outcomes and all-cause mortality in adults allocated to metformin: systematic review and collaborative meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Diabetologia. 2012 Oct;55(10):2593-2603. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2653-7. Epub 2012 Aug 10. Erratum in: Diabetologia. 2012 Dec;55(12):3399-400. PMID: 22875195.

[7] Griffin SJ, Leaver JK, Irving GJ. Impact of metformin on cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomised trials among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2017 Sep;60(9):1620-1629. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4337-9. Epub 2017 Aug 2. PMID: 28770324; PMCID: PMC5552849.

[8] Binnert C, Seematter G, Tappy L, Giusti V. Effect of metformin on insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in female obese patients with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes Metab. 2003 Apr;29(2 Pt 1):125-32. PubMed PMID: 12746632.

[9] Fruehwald-Schultes B, Oltmanns KM, Toschek B, Sopke S, Kern W, Born J, Fehm HL, Peters A. Short-term treatment with metformin decreases serum leptin concentration without affecting body weight and body fat content in normal-weight healthy men. Metabolism. 2002 Apr;51(4):531-6. PubMed PMID: 11912566.

[10] Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Christophi CA, Hoffman HJ, Brenneman AT, Brown-Friday JO, Goldberg R, Venditti E, Nathan DM. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009 Nov 14;374(9702):1677-86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. Epub 2009 Oct 29. Erratum in: Lancet. 2009 Dec 19;374(9707):2054. PubMed PMID: 19878986; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3135022.

[11] Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, Mukesh B, Bhaskar AD, Vijay V; Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme (IDPP). The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1). Diabetologia. 2006 Feb;49(2):289-97. Epub 2006 Jan 4. PubMed PMID: 16391903.

[12] O’Brien MJ, Perez A, Scanlan AB, Alos VA, Whitaker RC, Foster GD, Ackermann RT, Ciolino JD, Homko C. PREVENT-DM Comparative Effectiveness Trial of Lifestyle Intervention and Metformin. Am J Prev Med. 2017 Jun;52(6):788-797. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.008. Epub 2017 Feb 22. PMID: 28237635; PMCID: PMC5438762.

[13] Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study Research Group, Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Goldberg RB, Mather KJ, Marcovina SM, Montez M, Ratner RE, Saudek CD, Sherif H, Watson KE. Long-term effects of the Diabetes Prevention Program interventions on cardiovascular risk factors: a report from the DPP Outcomes Study. Diabet Med. 2013 Jan;30(1):46-55. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03750.x. PubMed PMID: 22812594; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3524372.

[14] Færch K, Blond MB, Bruhn L, Amadid H, Vistisen D, Clemmensen KKB, Vainø CTR, Pedersen C, Tvermosegaard M, Dejgaard TF, Karstoft K, Ried-Larsen M, Persson F, Jørgensen ME. The effects of dapagliflozin, metformin or exercise on glycaemic variability in overweight or obese individuals with prediabetes (the PRE-D Trial): a multi-arm, randomised, controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2021 Jan;64(1):42-55. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05306-1. Epub 2020 Oct 16. PMID: 33064182.

[15] Malin SK, Nightingale J, Choi SE, Chipkin SR, Braun B. Metformin modifies the exercise training effects on risk factors for cardiovascular disease in impaired glucose tolerant adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013 Jan;21(1):93-100. doi: 10.1002/oby.20235. PMID: 23505172; PMCID: PMC3499683.

[16] Pilmark NS, Oberholzer L, Halling JF, Kristensen JM, Bønding CP, Elkjær I, Lyngbæk M, Elster G, Siebenmann C, Holm NFR, Birk JB, Larsen EL, Lundby AM, Wojtaszewski J, Pilegaard H, Poulsen HE, Pedersen BK, Hansen KB, Karstoft K. Skeletal muscle adaptations to exercise are not influenced by metformin treatment in humans: secondary analyses of 2 randomized, clinical trials. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2022 Mar;47(3):309-320. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2021-0194. Epub 2021 Nov 16. PMID: 34784247.

[17] Moreno-Cabañas A, Morales-Palomo F, Alvarez-Jimenez L, Ortega JF, Mora-Rodriguez R. Effects of chronic metformin treatment on training adaptations in men and women with hyperglycemia: A prospective study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2022 Jun;30(6):1219-1230. doi: 10.1002/oby.23410. Epub 2022 May 17. PMID: 35578807.

[18] Konopka AR, Laurin JL, Schoenberg HM, Reid JJ, Castor WM, Wolff CA, Musci RV, Safairad OD, Linden MA, Biela LM, Bailey SM, Hamilton KL, Miller BF. Metformin inhibits mitochondrial adaptations to aerobic exercise training in older adults. Aging Cell. 2019 Feb;18(1):e12880. doi: 10.1111/acel.12880. Epub 2018 Dec 11. PMID: 30548390; PMCID: PMC6351883.

[19] Long DE, Peck BD, Tuggle SC, Villasante Tezanos AG, Windham ST, Bamman MM, Kern PA, Peterson CA, Walton RG. Associations of muscle lipid content with physical function and resistance training outcomes in older adults: altered responses with metformin. Geroscience. 2021 Apr;43(2):629-644. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00315-9. Epub 2021 Jan 18. PMID: 33462708; PMCID: PMC8110673.

[20] Walton RG, Dungan CM, Long DE, Tuggle SC, Kosmac K, Peck BD, Bush HM, Villasante Tezanos AG, McGwin G, Windham ST, Ovalle F, Bamman MM, Kern PA, Peterson CA. Metformin blunts muscle hypertrophy in response to progressive resistance exercise training in older adults: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial: The MASTERS trial. Aging Cell. 2019 Dec;18(6):e13039. doi: 10.1111/acel.13039. Epub 2019 Sep 26. Erratum in: Aging Cell. 2020 Mar;19(3):e13098. PMID: 31557380; PMCID: PMC6826125.

[21] Malin SK, Braun B. Impact of Metformin on Exercise-Induced Metabolic Adaptations to Lower Type 2 Diabetes Risk. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2016 Jan;44(1):4-11. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000070. PMID: 26583801.

[22] Preiss D, Lloyd SM, Ford I, McMurray JJ, Holman RR, Welsh P, Fisher M, Packard CJ, Sattar N. Metformin for non-diabetic patients with coronary heart disease (the CAMERA study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014 Feb;2(2):116-24. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70152-9. Epub 2013 Nov 7. PubMed PMID: 24622715.

[23] Hazuda HP, Pan Q, Florez H, Luchsinger JA, Crandall JP, Venditti EM, Golden SH, Kriska AM, Bray GA. Association of Intensive Lifestyle and Metformin Interventions With Frailty in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021 Apr 30;76(5):929-936. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa295. PMID: 33428709; PMCID: PMC8087265.

[24] Lee CG, Heckman-Stoddard B, Dabelea D, Gadde KM, Ehrmann D, Ford L, Prorok P, Boyko EJ, Pi-Sunyer X, Wallia A, Knowler WC, Crandall JP, Temprosa M; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group:. Effect of Metformin and Lifestyle Interventions on Mortality in the Diabetes Prevention Program and Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2021 Dec;44(12):2775-2782. doi: 10.2337/dc21-1046. Epub 2021 Oct 25. PMID: 34697033; PMCID: PMC8669534.

[25] Lexis CP, van der Horst IC, Lipsic E, Wieringa WG, de Boer RA, van den Heuvel AF, van der Werf HW, Schurer RA, Pundziute G, Tan ES, Nieuwland W, Willemsen HM, Dorhout B, Molmans BH, van der Horst-Schrivers AN, Wolffenbuttel BH, ter Horst GJ, van Rossum AC, Tijssen JG, Hillege HL, de Smet BJ, van der Harst P, van Veldhuisen DJ; GIPS-III Investigators. Effect of metformin on left ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction in patients without diabetes: the GIPS-III randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014 Apr 16;311(15):1526-35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3315. PMID: 24687169.

[26] Lexis CP, Wieringa WG, van der Horst IC, Willemsen HM, de Smet BJ, van den Heuvel AF, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Horst IC, Lipsic E, van der Harst P; GIPS-III Investigators. Effect of metformin on myocardial infarct size in patients without diabetes presenting with acute myocardial infarction: data from the Glycometabolic Intervention as adjunct to Primary coronary Intervention In St Elevation Myocardial Infarction (GIPS-III) trial. Submitted. Online resource: https://pure.rug.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/19453050/Complete_dissertation.pdf#page=44 Accessed 2022-06-30.

[27] Hartman MHT, Prins JKB, Schurer RAJ, Lipsic E, Lexis CPH, van der Horst-Schrivers ANA, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Horst ICC, van der Harst P. Two-year follow-up of 4 months metformin treatment vs. placebo in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: data from the GIPS-III RCT. Clin Res Cardiol. 2017 Dec;106(12):939-946. doi: 10.1007/s00392-017-1140-z. Epub 2017 Jul 28. PMID: 28755285; PMCID: PMC5696505.

[28] Griffin SJ, Bethel MA, Holman RR, Khunti K, Wareham N, Brierley G, Davies M, Dymond A, Eichenberger R, Evans P, Gray A, Greaves C, Harrington K, Hitman G, Irving G, Lessels S, Millward A, Petrie JR, Rutter M, Sampson M, Sattar N, Sharp S. Metformin in non-diabetic hyperglycaemia: the GLINT feasibility RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2018 Apr;22(18):1-64. doi: 10.3310/hta22180. PMID: 29652246; PMCID: PMC5925436.

[29] Lamanna C, Monami M, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. Effect of metformin on cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011 Mar;13(3):221-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01349.x. PMID: 21205121.

See also the other posts in this series:

- Part 1: on the animal data on metformin and aging;

- Part 3: on human trials of metformin to prevent or treat cancer;

- Part 4: on human studies on metformin and age-related cognitive decline and dementia; and

- Part 5: on the backstory on TAME and how it might impact the push for longevity therapeutics.

- Addendum: More Studies on Metformin and Survival

- Addendum: Monkeying With the Clocks Via Metformin